OSCILLATORS & AVERAGES

When it comes to market timing there are endless options to choose from. Even those who are inclined to trade based upon fundamentals will often use some form of trend validation using their favourite technical approach. There is certainly no shortage of literature available on the topic and we would encourage all to enhance their understanding by checking out the extensive resources available online. Traders may often jump from one indicator to another in a quest to find the optimal timing tool but, in my experience, it is better to choose very few, understand their behaviour, and act upon your knowledge base to improve timing skills. Let’s start by have a brief look at what some of the options are.

Oscillators for extremes

These are standalone mathematically generated formulas which can visually represent the performance of a security and will often have a maximum and minimum value, though not always e.g. a minimum value of 0 and a maximum value of 100. Again, there is too much information available on this subject to explore here but, for the purpose of illustration and simplicity, I will mention 2 of the most popular.

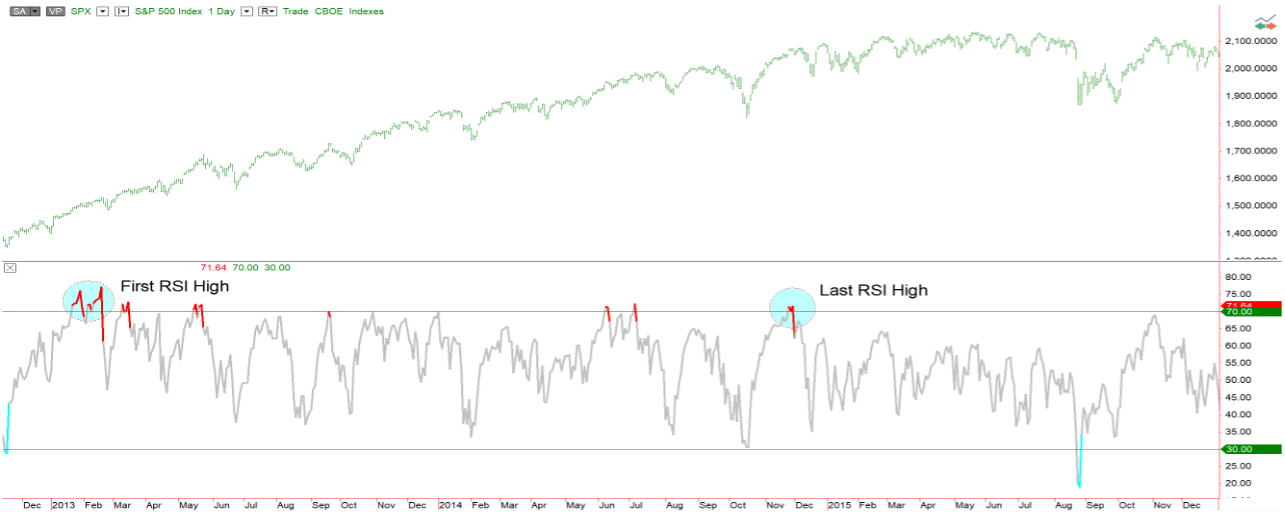

Firstly, the RSI (Relative Strength Index) – This is essentially an indicator which compares average gains against average losses over a fixed period (Usually 14 days or bars). With a range of 0 to 100, the general wisdom is that a reading above 70 represents an ‘overbought’ situation for the price data applied, and below 30 equals ‘oversold’. Like many static indicators, there are times where this works very well and others where quite the opposite approach would work better.

The chart below shows the RSI for the S&P 500 index from 2013 through 2015. From this graph, it is clear to see that using the 70 / 30 extremes as specific points to sell or buy would have resulted in some very poor trades. The first ‘overbought’ point was at an index level of ~1,500 and the final point registered at ~2,000 > 30% higher. Numerous such extreme levels occurred several times in between, providing what are effectively false signals which might encourage some to sell long positions too early, or indeed short with the expectation of lower levels ahead. On a standalone basis, this highlights the challenge of using such rangebound oscillators as timing points. In this basic format, they will tend to work best in range bound markets.

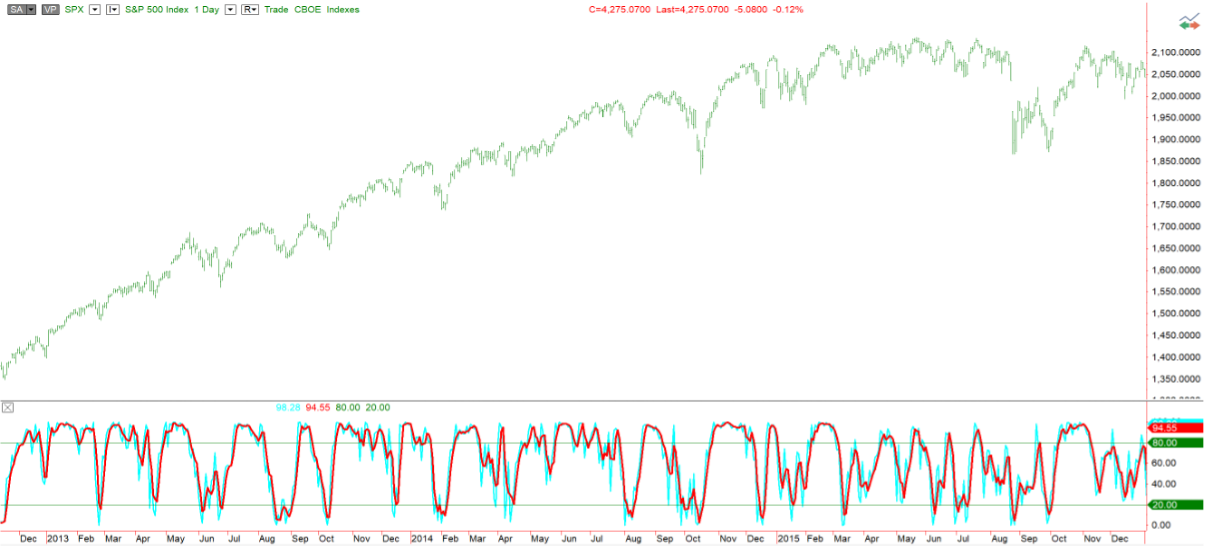

Another similar style oscillator with multiple variations is the Stochastic indicator. In its most simple form (FastK), it can be considered as a location reference type indicator. It looks at the highest and lowest points over a look back period, and simply references, in a percentage format, the current location of the price versus the extremes. For example, if the highest stock price in the past x days is 100, the lowest price is 50, and the current price is 75 (directly in the middle of the extremes), then the indicator will register 50 (%) as it is precisely halfway between the top and the bottom.

The indicator has a ‘smoothed’ version (FastD) too, which is effectively an average of the ‘FastK.’ Smoothing will ordinarily be a simple moving average of the last few data points. However, as will be discussed later, such smoothing can have the drawback of delayed signalling in the form of slower reaction times for changes in trend. The graph below shows the Stochastic Oscillator covering the same data as the above graph for basic comparison purposes.

To conclude, there are many oscillators beyond the scope of this very brief introduction. They will often be used to signal extreme points where some type of price reversion may occur. From the simple example above, as standalone indicators, there are obvious problems using these within strong trends but, as you will see later, they can have their uses, particularly when complimenting trending methodologies which have different characteristics.

Averages for direction

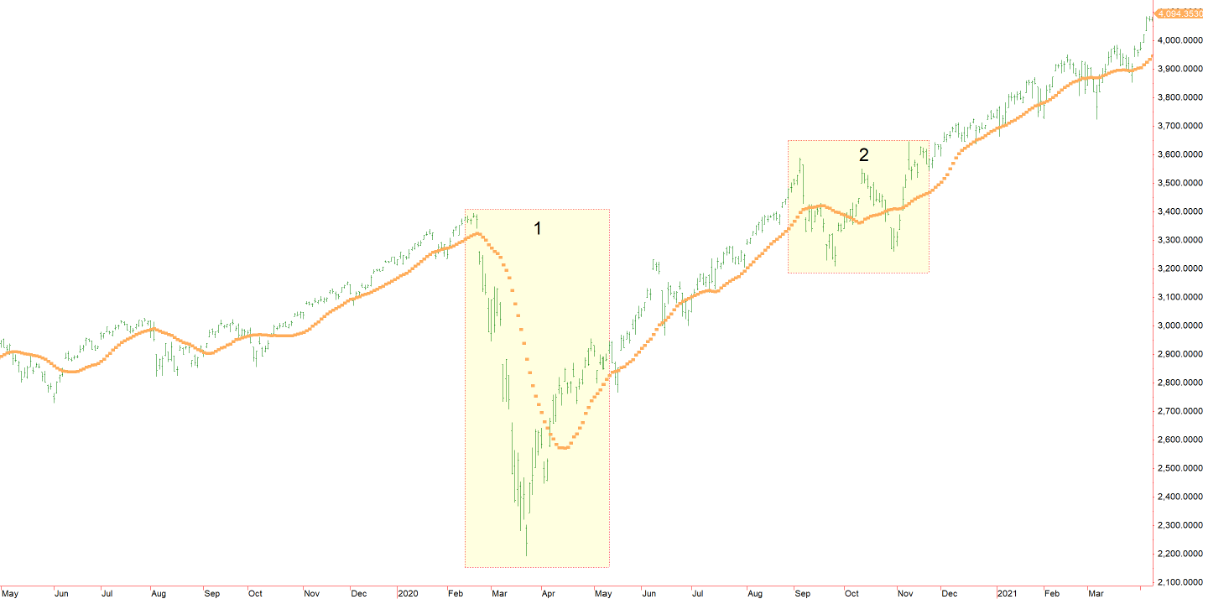

Unlike oscillators, the use of Moving Averages, and the many derivative indicators they inspire, are predominantly used for the purpose of trend recognition. A Simple Moving Average (SMA) is very basic yet can be visually very useful when determining market direction. It is calculated by choosing a look back period, for example 20 days / bars. Then, the average closing price of that period is calculated and plotted within the primary chart price data. As each bar moves forward, the newest bar is added to the latest calculation, while the oldest bar is excluded to ensure the average calculated is equal to the number of bars specified. This is then plotted in a continuous line representing the data series. The graph below is a snapshot of the S&P 500 index which shows how well a moving average determines and follows trends. I have also highlighted a couple of areas for closer scrutiny to demonstrate that sometimes the visual appearance can blur some of the issues that may not be always apparent.

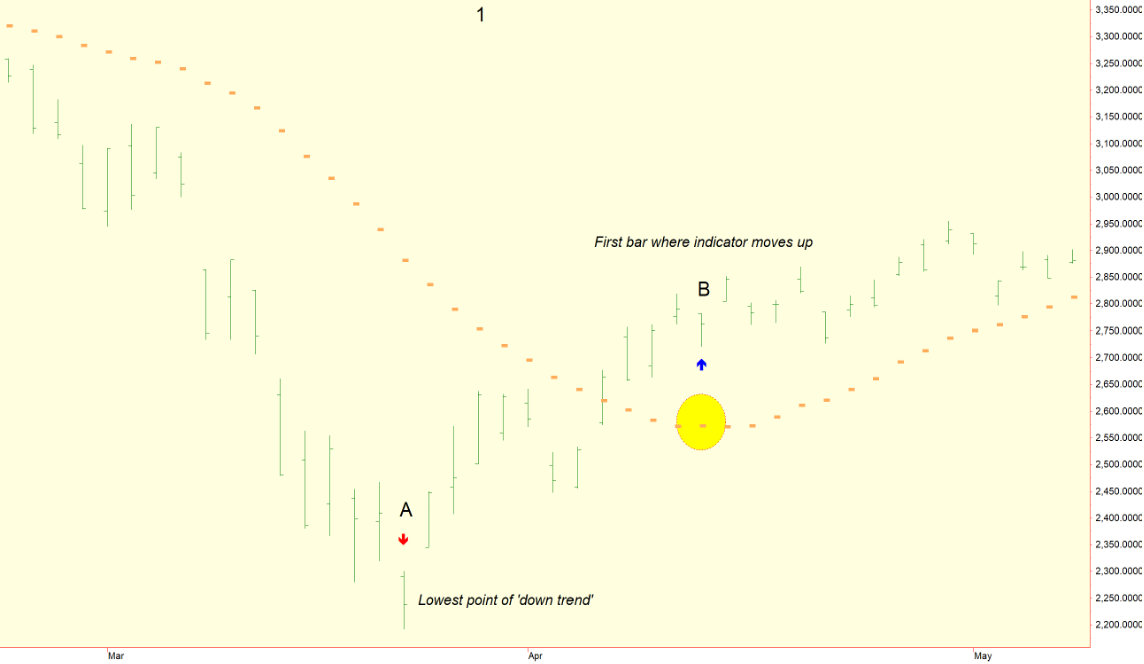

- If we expand the highlighted area ‘1’, we can see from the image below one of the issues that tends to occur with this kind of indicator.

It’s reliance on past data offers a limited insight into upcoming directional changes. It can follow past movements but, to determine a trend has changed, it can only do so after a significant number of bars have passed. In this example, let’s assume the trend is determined by the average’s movements from the previous bar (Higher= Positive and Lower=Negative). As you can see, point A is the lowest actual closing price in the downward trend - ~2,250. Point B represents the first time the average is higher than that of the previous bar, indicating a positive trend. Closing price is ~2,750. Although this is a somewhat extreme example, in the 12-day period from the low point to the indicator turning positive, there has been a price change of >20%. It lacks sensitivity, which is true of all trend following indicators in varying degrees.

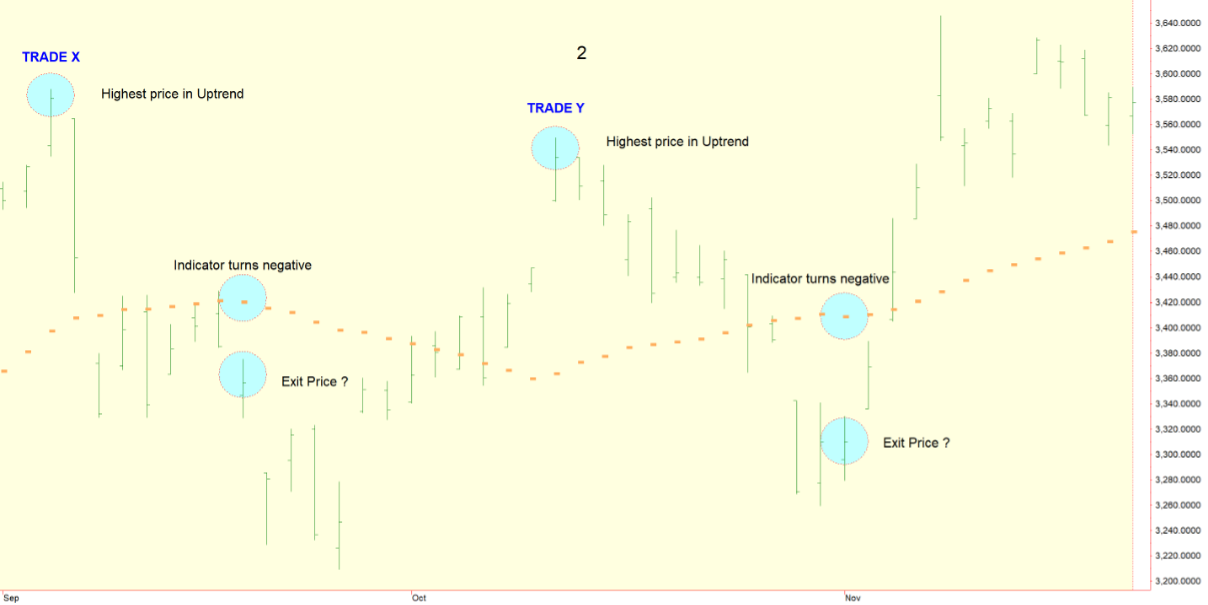

- If we look at the second highlighted example (Above), a point at which the markets strong directional bias had visually reduced, I have highlighted what could have been 2 exit trades based on theoretical pre-existing entries. Once again, for Trades X and Y, the highest point in the uptrend has been circled, along with the exit point where the indicator turns down. For trade X, the time it took for the indicator to turn to exit the trade was 8 bars (with ~8% price difference) and for trade Y, the time was equal to 12 days (and ~10% lower than the peak levels). If we consider that the same type of price differential might occur on entries as well, then we are looking at a large swing from the potential maximum P&L. In these 2 examples, the peak to trough maximums (High v Low differential) within the trade periods would have to be around 20%. This time lag represents a huge opportunity cost which may make such a trade worthless. Despite this, however, moving averages in general do provide a good visual representation of the trends. Many statistical models will use them to define general trend and then use other indicators to search for extremes, only taking trades in the direction of the trend defined by the averages.

-

All the above just skims the surface of these topics, but provides a basic understanding required at this point. There are many different types of moving average available for study, and each can be used in different ways. Moving averages crossovers, Convergence and divergence are just a couple of related topics which may be worth an internet search and should generate more than enough material to think about. The main point is to understand that trends can only be determined after they have moved in a certain direction using historical data as a reference point, but there is a significant cost associated because of the inherent time lag to reach the point of recognition.

- Practical uses of Oscillators and Averages

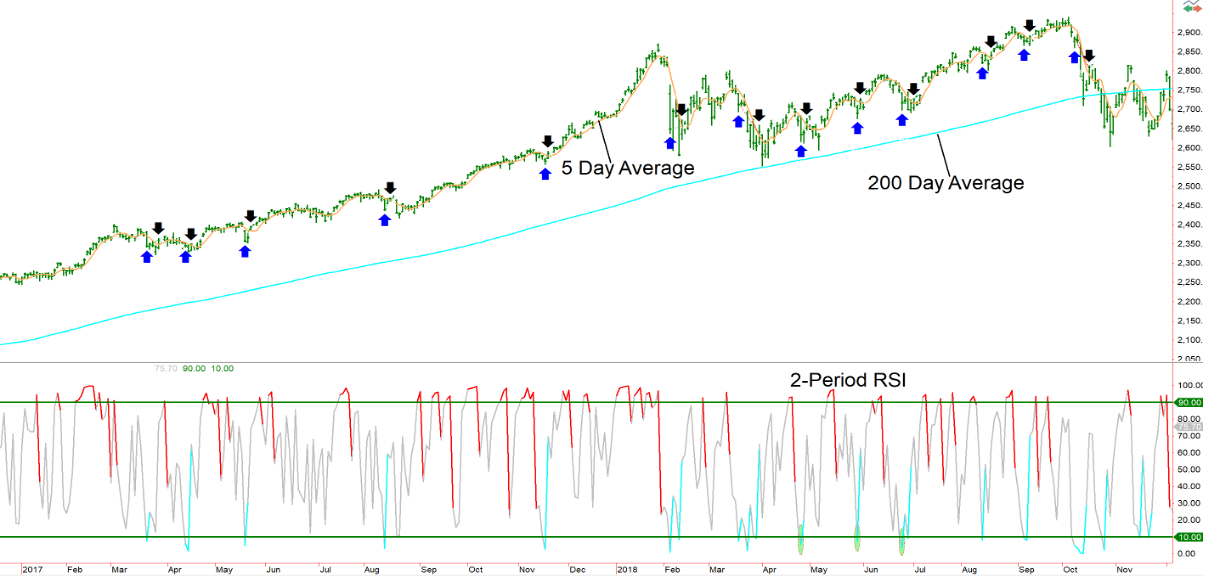

Having read the above, you might be forgiven for thinking that neither of the above themes are worthy of pursuit due to their inherent pitfalls, however, the opposite is true. When combined, Averages and Oscillators can make interesting short-term strategies. There are many vendors who sell such strategies and, although some are better than others, the principles are generally consistent and valid. Basically, these are mean reverting strategies. Oscillators are used to determine the extreme where a stock (or index) might be bought or sold, and the trade should be exited once this extreme has rectified itself by reverting to the short-term average. To give a bit more explanation, let us look at one of the most well-known strategies of this type, namely the 2-period RSI strategy. It is based on a strategy attributed to Larry Connor’s who has written extensively on the topic of market timing.

For the purposes of simplicity and to demonstrate the power, I have employed a ‘Long only’ version (only buy signals) of the strategy and tested using the S&P 500 closes as the data set, back to 1998.

The rules for the Long Only system are as follows ……...

1) The closing price must be > 200 day moving average. This is to trade in the general direction of the trend.

2) The 2-period RSI must have a reading below 10 i.e., buying at a short term ‘extremely oversold’ level.

3) The trade can be closed when the close > 5 day moving average.

The above is a visible representation of how this looks when applied to a chart. The blue arrows are entry points, while the black arrows represent exits. When RSI indicator is below and the solid green line at the bottom this represents the ‘Oversold’ area. Now let us have a closer look ………

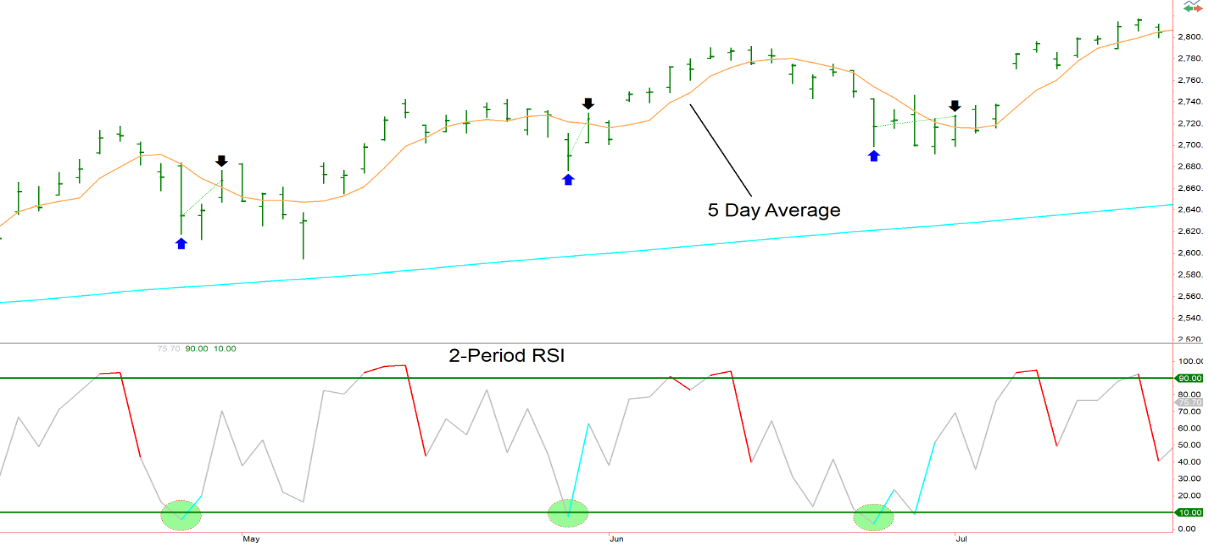

This view makes it easier to see the RSI closing below the ‘10’ thresholds, triggering buy signals, and the exits on the first close trading above the 5-day moving average.

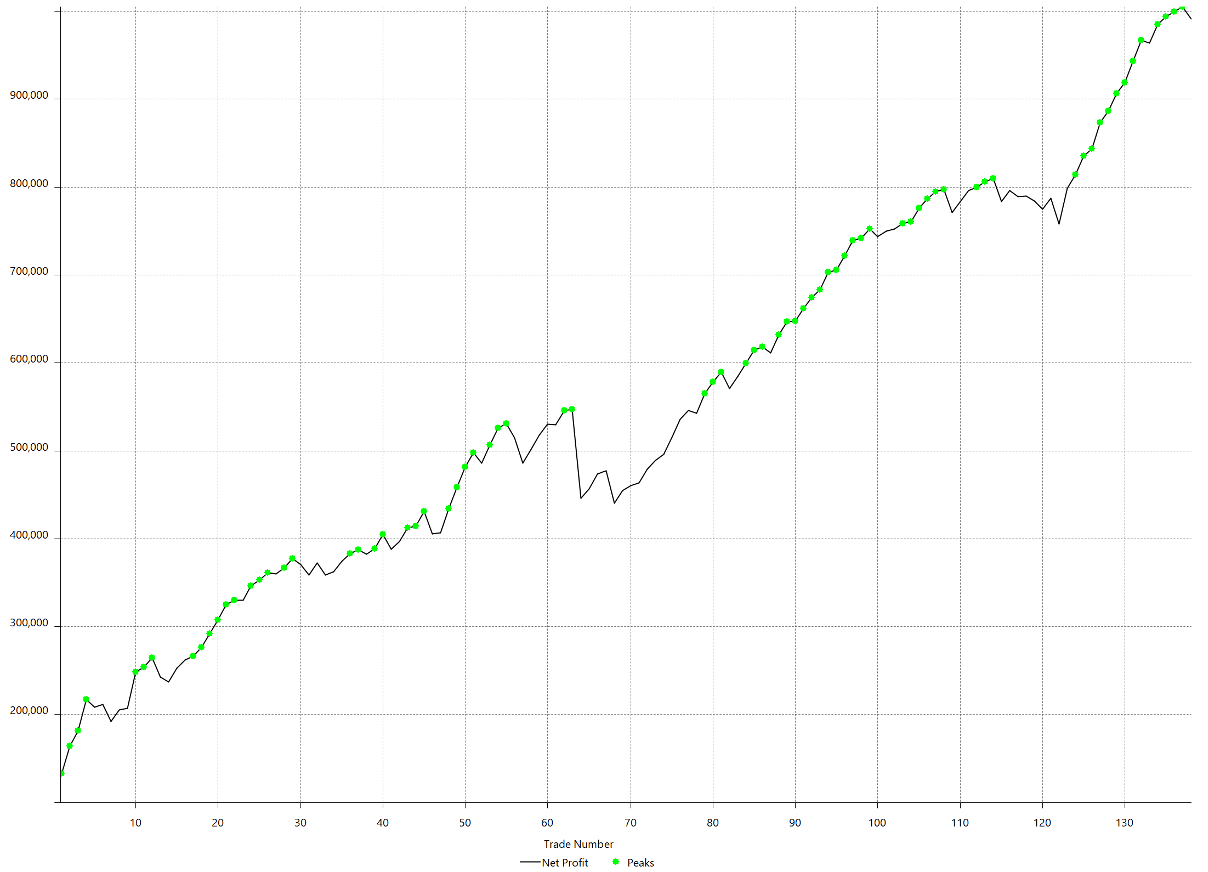

So, let us look at the performance of this very simple rule-based strategy.

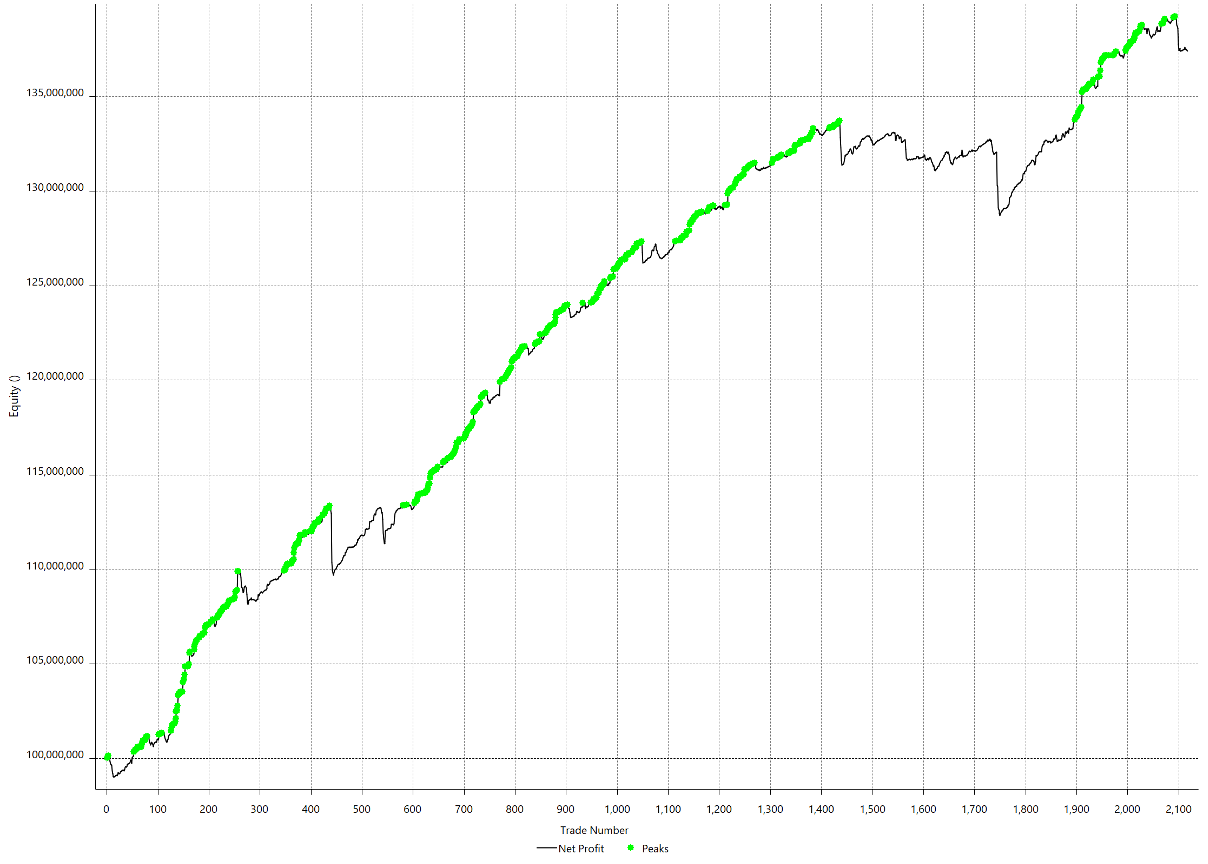

This is the close-to-close performance over the ~ 25-year testing period. 78.26% of trades were winners with an average return of 65 basis points (assuming equal trade size throughout). What is also interesting is that this strategy has no stops for either profit or loss. Its strength is clearly the high percentage of winners and short holding period.

Now, let us use the exact same strategy against a basket of stocks. For this test we are using the components of the S&P 100 index going back to 2007.

Again, we see the close-to-close performance over the period. 69.15% of trades were profitable, returning 43 basis points on average per trade. Although the equity line is not as smooth, it still seems quite amazing that a simple strategy like this, which uses the same parameters for each component, can be so seemingly robust.

We will revisit this topic a little later when we look at statistical strategies but, for now, the purpose of this section has been to demonstrate that, although some indicators have their challenges when in isolation, predominantly based on whether they are proactive (RSI extremes) or reactive (Moving average trends), they can often combine to good effect.

As an addendum, when trading large numbers of stocks professionally, or indeed creating an expansive personal portfolio, indicators and back tested strategies are excellent tools to help focus in on assets in a timely manner – A kind of highlight list for additional scrutiny, as this process can be automated and will save immeasurable time when deciding what to trade for the here and now. Throughout this site, such back tested strategies will be explored and be included within daily updates to sharpen focus on what to trade, and when.

Again, this all-forms part of the ‘Prep’ process and is just as important as the actual trading part.